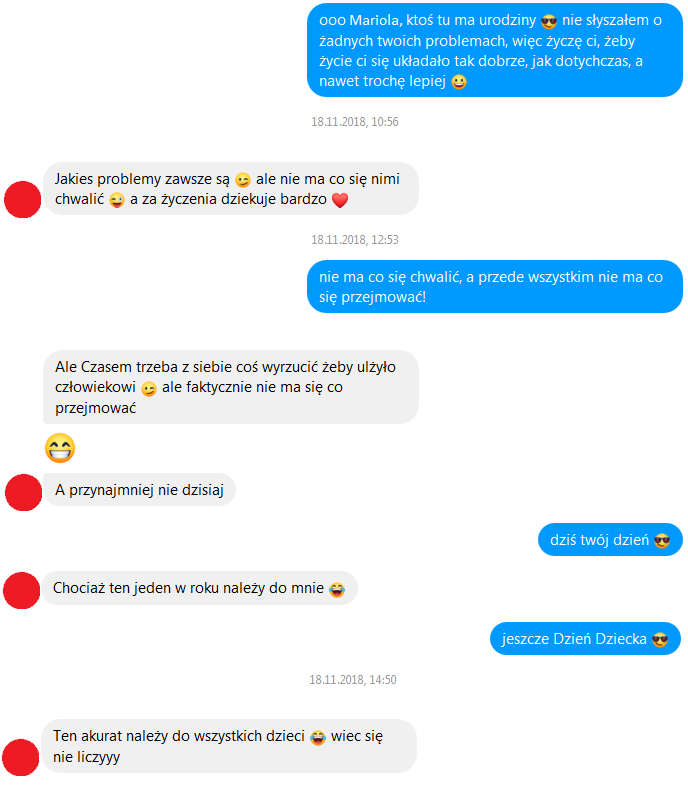

Welcome to the second lesson from the series „Learn Polish through private messages”! Today we will see how a Polish native speaker reacted to birthday wishes.

First let’s read the chat. Click, read it, try to understand and then learn the missing parts.

Comparing to the first conversation we saw, here we will see less diacritical mistakes. It should let you understand the chat better. I hope you understood quite a lot!

„Ktoś tu ma urodziny” — of course this „someone” whose birthday it is is the recipient of the message. It’s a little cheeky way of saying „I noticed it’s your birthday”.

„Życzę ci, żeby życie układało ci się tak dobrze, jak dotychczas” — there are two a little difficult words here. „Układać się” is the first one. It literally means „to lay itself” or „to arrange itself”, but you shouldn’t understand it this way. The real meaning is „to go well”. We use it almost always with „życie” („life”), sometimes with „praca” („job”) or „podróż” („trip”). Sometimes we omit the subject and just say for example: „Życzę ci, żeby układało ci się dobrze” — the subject is implicit and this subject is „life”. „Układać się” is an imperfective verb. Its perfective form is „ułożyć się”.

The second difficult word in this sentence is „dotychczas”. It’s interesting because we can break it down and get: do + tych + czas. Notice that if add „ów” at the very end, we’ll get a logical and grammatically correct expression: „do tych czasów” which would mean „to these times”. And „dotychczas” means it too. It means „up to now”. You can also get down „(jak) na razie” — it has the same meaning.

„Nie ma co się nimi chwalić” — this is an interesting expression: „nie ma co”. „Nie ma co” (literally „there’s no what”) alone is an exclamation which means ironic „absolutely”, „right”. For example one can say: „On jest super, nie ma co” — „He’s great, absolutely”. Notice that we defined „nie ma co” as ironic, so this „absolutely” is ironic — so is the whole sentence.

Buuuuuuut in our sentence „Nie ma co się nimi chwalić” the expression „nie ma co” conveys a different meaning. „Nie ma co” means „There’s nothing to (do something)” too. The verb here is „chwalić się” (kim? Czym?) which means „brag about”. It’s imperfective and its perfective form is „pochwalić się”. The whole sentence means „There’s nothing to brag about”. „Nimi” which means „by them” can be omitted. In the English translation there’s no proper place to put this word. If you really want to include this word, you can translate it as „Bragging about them is not appropriate”.

„Nie ma co się chwalić, a przede wszystkim nie ma co się przejmować” — here we can see the same pattern „nie ma co”, but there are also two new phrases. „Przede wszystkim” means „above all” or „in the first place” and it’s an absolute must–learn. It’s an extremely common expression. The last word in this sentence is „przejmować się” (kim? Czym?) which is an imperfective verb. Its perfective form is „przejąć się”. This verb means „to care (about something)”, „to worry”. Maybe you heard a different word which means the same: „martwić się”.

„Czasem trzeba z siebie coś wyrzucić, żeby ulżyło człowiekowi” — this is not the easiest. „Wyrzucić” means „to throw away”. It’s perfective and its imperfective form is „wyrzucać”. However, we must consider „wyrzucić z siebie” as whole. „Wyrzucić z siebie” is „to spew out”, that is „to say out loud words of heavy emotions”. Here we’ve got „wyrzucić COŚ z siebie”, but this „coś” are always emotions. Nonetheless, this verb is transitive and it cannot exist without an object (one or another). So the person must say „wyrzucić coś z siebie”.

„Trzeba” — do you know this word? It’s not that advanced, it means „one must”, „one should”, „you should”, these things. „Czasem trzeba z siebie coś wyrzucić” altogether means „Sometimes one must let the emotions out”. At the end of the whole sentence we can read „aby ulżyło człowiekowi”. „Ulżyć” (komu? Czemu?) is a verb we almost always use without a subject, but almost always with an object. „Ulżyć” means „to relieve”. „Żeby ulżyło człowiekowi” together means „to give a person relief”.

Wow, there are so many difficult expressions here! Let’s introduce the last one. In the last message there’s „Ten akurat należy do wszystkich dzieci”. „Akurat” seems similar to „accurate”, but the use is very different. „Akurat” has many uses and I don’t want to write about them all here, I’ll just explain what it means in this specific sentence. We use it when first we introduce some generalisation and later we want to give an example which doesn’t follow the general rule. It might be not very clear in this conversation, because it wasn’t said explicitly, but the generalisation is: „No day of a year (besides my birthday) belongs to me”. The second person opposes: „But Childrens’ Day belongs to you!”. This is an example which doesn’t follow the general rule. The second person didn’t use the word „akurat”, but they could. Then the first person responds: „This day akurat belongs to all children”. „Akurat” refers to the isolated example of a day which does belong to the first person.

I want to give you two more dialogues with „akurat” in order that you understand this word better.

— Grenlandia jest największą wyspą na świecie.

— Australia jest większa!

— Australia akurat nie jest wyspą.

— Samochodem ogólnie jedzie się szybciej niż pociągiem, ale dzisiaj akurat są korki.

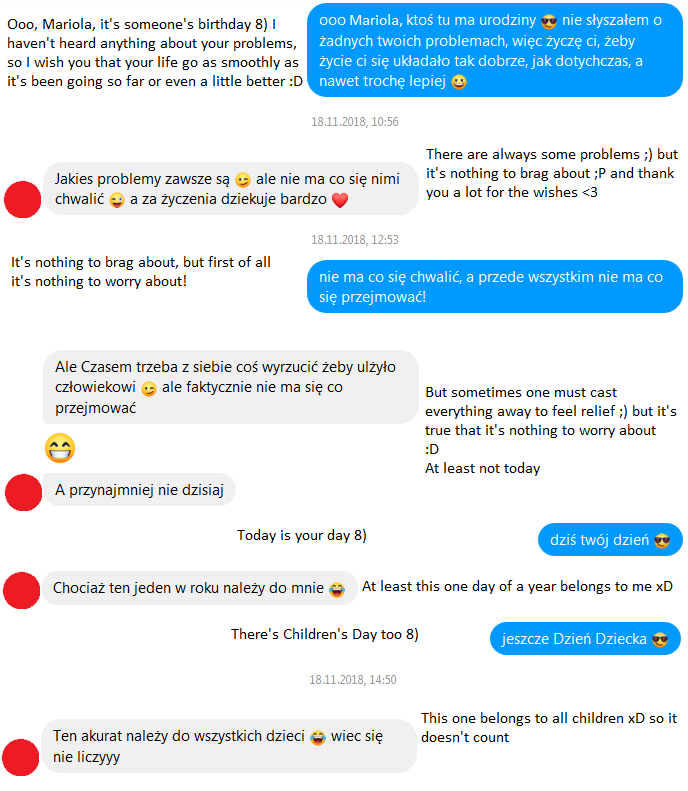

And that’s all! If you’ve got any further question — ask them here! At the bottom you’ll find complete translation of this chat.

Comment the post here or on Facebook.

The image comes from flickr.com.